This is a purely speculative exercise, of course; Lynnleigh's's face is still thin, and doesn't have much the muscle or fat that will give it shape yet. But even wild speculation is fun. Here she is, side by side with her sister:

Monday, November 8, 2010

Follow-Up

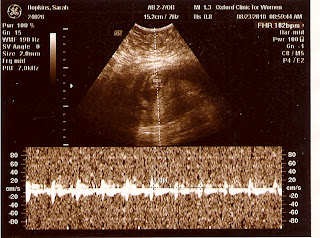

We went back to the perinatologist today. Last time everything looked good, but her heart was just the size of a quarter, so they couldn't see all the details they wanted to see. This time they had a closer look at the valves in her heart and the arteries leading into and out of it. The news is all good: everything looks as it should.

Pictures:

With that, we're all done with the perinatologist, and back to just visiting our local OB. That probably means these are the last pictures for a good long while. But that's OK; Sarah can feel the baby move every day now, so we have some constant reassurance that she's still in there and doing well.

Pictures:

With that, we're all done with the perinatologist, and back to just visiting our local OB. That probably means these are the last pictures for a good long while. But that's OK; Sarah can feel the baby move every day now, so we have some constant reassurance that she's still in there and doing well.

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Perinatologist

At our last appointment with the fertility doc, he suggested that we look into having a fetal echocardiogram done around Week 18.

Backstory: Our first daughter, Ainsleigh Brynn, was born with a "constellation" of heart defects that ultimately combined to kill her. There's about a 5% recurrence rate for congenital heart defects. That's not a lot, and there's little to be done about it in utero anyway. However, we live in a small town; our hospital doesn't have a NICU and the nearest pediatric cardiologist is at LeBonheur in Memphis. So, the thinking is: find out if there are any problems, so that we can be prepared --- where in this context "prepared" means, crucially, that we'd arrange to have the baby in Memphis at a hospital that can support the baby.

Our OB agreed with the fertility doc, and so referred us to a perinatologist in Memphis. We had that appointment yesterday, October 11th. It went very well.

The ultrasound itself lasted about an hour and a half. The tech told us baby is a girl first thing.

Then she checked out the baby in every dimension. For instance, she counted all the fingers and toes.

There were lots of other checks, too. She confirmed that baby has two umbilical arteries (this is the correct number; Ainsleigh only had one), that her kidneys are in place a supplied with blood (she can watch blood flow through the renal arteries), that her spine is properly formed, and more.

One thing they do is estimate the baby's size. The tech takes three measures: the circumference of the head, the circumference of the abdomen, and the length of the femur. Each measurement is used to form an independent estimate of baby's weight. These estimates are averaged; the average comes to 10 oz. This figure is looked up on a chart ; it corresponds to the average size of a baby at a gestational age of 19 weeks. Given that baby was 18 weeks 5 days at the time of the ultrasound, she's right on time.

In addition to the 2-D images taken at a particular depth, they can rapidly scan through depths and use the computer to construct a 3-D portrait of baby:

It's imperfect, of course, but you can see her pretty well here.

As to the purpose of the visit: her heart looks great. They spend a great deal of time on this. There are a number of techniques involved. A simple ultrasound can show the heart moving as it beats, and the valves opening and closing. The machine can also detect the movement of blood through the major blood vessels as well as between the chambers of the hearts. Finally, they can zero in on and listen to the various components of the heartbeat: this or that valve opening and closing in rhythm. The amount of detail that can be gleaned is really impressive, given baby's heart is about the size of a quarter.

Put all these approaches together and you get the result you want: baby is healthy, and her heart is in perfect working order.

Backstory: Our first daughter, Ainsleigh Brynn, was born with a "constellation" of heart defects that ultimately combined to kill her. There's about a 5% recurrence rate for congenital heart defects. That's not a lot, and there's little to be done about it in utero anyway. However, we live in a small town; our hospital doesn't have a NICU and the nearest pediatric cardiologist is at LeBonheur in Memphis. So, the thinking is: find out if there are any problems, so that we can be prepared --- where in this context "prepared" means, crucially, that we'd arrange to have the baby in Memphis at a hospital that can support the baby.

Our OB agreed with the fertility doc, and so referred us to a perinatologist in Memphis. We had that appointment yesterday, October 11th. It went very well.

The ultrasound itself lasted about an hour and a half. The tech told us baby is a girl first thing.

Then she checked out the baby in every dimension. For instance, she counted all the fingers and toes.

There were lots of other checks, too. She confirmed that baby has two umbilical arteries (this is the correct number; Ainsleigh only had one), that her kidneys are in place a supplied with blood (she can watch blood flow through the renal arteries), that her spine is properly formed, and more.

One thing they do is estimate the baby's size. The tech takes three measures: the circumference of the head, the circumference of the abdomen, and the length of the femur. Each measurement is used to form an independent estimate of baby's weight. These estimates are averaged; the average comes to 10 oz. This figure is looked up on a chart ; it corresponds to the average size of a baby at a gestational age of 19 weeks. Given that baby was 18 weeks 5 days at the time of the ultrasound, she's right on time.

In addition to the 2-D images taken at a particular depth, they can rapidly scan through depths and use the computer to construct a 3-D portrait of baby:

It's imperfect, of course, but you can see her pretty well here.

As to the purpose of the visit: her heart looks great. They spend a great deal of time on this. There are a number of techniques involved. A simple ultrasound can show the heart moving as it beats, and the valves opening and closing. The machine can also detect the movement of blood through the major blood vessels as well as between the chambers of the hearts. Finally, they can zero in on and listen to the various components of the heartbeat: this or that valve opening and closing in rhythm. The amount of detail that can be gleaned is really impressive, given baby's heart is about the size of a quarter.

Put all these approaches together and you get the result you want: baby is healthy, and her heart is in perfect working order.

Movement

Sarah started feeling the first movement about three weeks ago, during Week 15. (This writing is at the end of week Week 18.) Since then the movement has gotten more frequent and more noticeable. Now Sarah can feel movement several times a day. Frankly she enjoys the Hell out of it.

I think I felt the baby move very early on, in Week 16 or so. I had my hand on Sarah's stomach and felt a soft but definite rolling --- sort of like baby had been under my hand and then rolled out from under it. Since then, I haven't been able to feel anything. Occasionally Sarah will say "come her, the baby is kicking" and I'll run over and put my hands on her belly, but then baby always immediately stops kicking. Oh, well; it will come in time.

I think I felt the baby move very early on, in Week 16 or so. I had my hand on Sarah's stomach and felt a soft but definite rolling --- sort of like baby had been under my hand and then rolled out from under it. Since then, I haven't been able to feel anything. Occasionally Sarah will say "come her, the baby is kicking" and I'll run over and put my hands on her belly, but then baby always immediately stops kicking. Oh, well; it will come in time.

Some Limited Excitement

The sonogram on 17 August really wasn't supposed to happen. As previously discussed, we 'graduated' from the fertility doctor on Monday, August ninth. Thereafter we immediately made an appointment with Sarah's regular OB here in Oxford. That appointment was on August seventeenth.

This appointment was meant to be a meeting. But halfway through the meeting, the doc was called away to do a delivery. So, he had his tech do an ultrasound to keep us amused while he was gone. There was nothing terribly informative about the resulting pictures, but it was nice to see the baby, as it always is.

Five days later, on Sunday the 22nd, Sarah had some bleeding. There wasn't a terribly huge amount, and she didn't have any cramping or pain with it. Nevertheless, Sarah was very scared and called the doc. He told her not to stress out about it, to take it easy the rest of the day and come in first thing Monday morning.

By then, the bleeding had stopped and we were starting to settle down. But, they did an ultrasound to peek in on baby anyway. As expected, all was in order.

This appointment was meant to be a meeting. But halfway through the meeting, the doc was called away to do a delivery. So, he had his tech do an ultrasound to keep us amused while he was gone. There was nothing terribly informative about the resulting pictures, but it was nice to see the baby, as it always is.

Five days later, on Sunday the 22nd, Sarah had some bleeding. There wasn't a terribly huge amount, and she didn't have any cramping or pain with it. Nevertheless, Sarah was very scared and called the doc. He told her not to stress out about it, to take it easy the rest of the day and come in first thing Monday morning.

By then, the bleeding had stopped and we were starting to settle down. But, they did an ultrasound to peek in on baby anyway. As expected, all was in order.

Catching Up

Apologies are in order. I started a new job last month, and I've been extremely busy. Since the last posting, we've had three sonograms. In the last (no use trying to build suspense when I've already colored the blog pink) we found out: baby is a girl. Now, in order, pictures from each sonogram, and some other stuff.

Tuesday, August 10, 2010

Travel Notes

From our initial consultation on March 1st, I count 19 round trips to the fertility clinic. Per Google Maps, the clinic is 75.6mi from home; that's a total of ~2870mi for this cycle. Put another way, at 1.5hr each way, it's 57hr in the car.

Graduation Day

We had the last of our early ultrasounds yesterday. First, the picture.

My usual annotated copy.

Baby is head-down and facing to your left. From head to rump, baby measures 3.03cm. That's 1.19in, and corresponds to an age of 9 weeks, 6 days. As of yesterday, baby's actual age was 9 weeks, 5 days (this moment in hyper-precision brought to you by in vitro fertilization!), so we're right on schedule. Live, you can see baby's heart beating and his/her arms and legs moving. The heartbeat, at 175 bpm, is right where it ought to be. The arm and leg movement has triggered a running gag around my house about baby waving to us, and then kicking in a "OK, I said hello, now get out of here" motion.

With all these right-on-schedule measurements, our IVF doc has decided to turn Sarah over to her regular OB. So we're all done with the fertility clinic for this go-round. We don't expect to return to the clinic until the biannual "baby party" at Mother's Day next year.

My usual annotated copy.

Baby is head-down and facing to your left. From head to rump, baby measures 3.03cm. That's 1.19in, and corresponds to an age of 9 weeks, 6 days. As of yesterday, baby's actual age was 9 weeks, 5 days (this moment in hyper-precision brought to you by in vitro fertilization!), so we're right on schedule. Live, you can see baby's heart beating and his/her arms and legs moving. The heartbeat, at 175 bpm, is right where it ought to be. The arm and leg movement has triggered a running gag around my house about baby waving to us, and then kicking in a "OK, I said hello, now get out of here" motion.

With all these right-on-schedule measurements, our IVF doc has decided to turn Sarah over to her regular OB. So we're all done with the fertility clinic for this go-round. We don't expect to return to the clinic until the biannual "baby party" at Mother's Day next year.

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Other News

After Monday's ultrasound, we also met with our doctor. The results of that meeting:

1. No more shots; Sunday's progesterone injection was the last shot for this cycle.

2. The other hormone supplements are to be stepped down over the next two weeks.

3. We go back for one more sonogram and meeting with Dr. Ke on Monday August 9th; this is expected to be the last trip to the fertility clinic in Memphis.

4. We're to be handed over to our local OB effective August 17th, when we have our first appointment with him.

So all is well, I think. Did I miss anything?

1. No more shots; Sunday's progesterone injection was the last shot for this cycle.

2. The other hormone supplements are to be stepped down over the next two weeks.

3. We go back for one more sonogram and meeting with Dr. Ke on Monday August 9th; this is expected to be the last trip to the fertility clinic in Memphis.

4. We're to be handed over to our local OB effective August 17th, when we have our first appointment with him.

So all is well, I think. Did I miss anything?

Monday's Ultrasound

We had another sonogram on Monday the 26th. A picture, shot with my iPhone:

A marked-up version so you'll know what you're looking at:

Baby is still doing well; 1.34cm in length, with a heartbeat of 166bpm, and a very recognizable person-shape. (Here, picture a baby laying on his right side.) All signs are good.

A marked-up version so you'll know what you're looking at:

Baby is still doing well; 1.34cm in length, with a heartbeat of 166bpm, and a very recognizable person-shape. (Here, picture a baby laying on his right side.) All signs are good.

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

One Baby

Last Thursday, we went and had an ultrasound to settle the critical "one baby or two" question. Here is the result of that test:

Unhelpful, right? Like a snowy TV, really. Here. let me give you a hand:

The picture shows one baby (because that's what we're having: one baby). Don't be tempted to think the little peanut-shaped bright structure (the yolk sac, labeled here) is the baby; it's not. The baby is a darker mass up from and left of the yolk sac. I know this because, from inside the room, you can see the baby's tiny heart beating right in that area. The heartbeat was good and strong --- a particular concenr of ours, given our personal history.

For scale, I've labeled the gestational sac, which is 1.7cm in length. The baby here is about 0.3cm in length -- the size of a small coffee bean. For this reason Sarah briefly took to referring to baby as "Latte Hopkins."

Unhelpful, right? Like a snowy TV, really. Here. let me give you a hand:

The picture shows one baby (because that's what we're having: one baby). Don't be tempted to think the little peanut-shaped bright structure (the yolk sac, labeled here) is the baby; it's not. The baby is a darker mass up from and left of the yolk sac. I know this because, from inside the room, you can see the baby's tiny heart beating right in that area. The heartbeat was good and strong --- a particular concenr of ours, given our personal history.

For scale, I've labeled the gestational sac, which is 1.7cm in length. The baby here is about 0.3cm in length -- the size of a small coffee bean. For this reason Sarah briefly took to referring to baby as "Latte Hopkins."

Friday, July 2, 2010

Twinning

Because it's come up in a couple of Facebook comments, I want to say a word or two about the upper bound on the number of babies Sarah might be carrying.

The short answer is: two. The doc transferred two embryos. If they've both survived, then Sarah's carrying twins; if only one has survived, then it's just one baby (for this time).

The longer answer is: well, it depends. There were two blastocysts on Day 5. Most identical twinning is thought to happen at the blastocyst stage between Days 4 and 8. The astute reader will note that 5 is more than 4 but less than 8; this means it is at least possible for a day Day 5 blast to split into monozygotic (identical) twins after the transfer. So it's possible, in the strictest sense of the word, that Sarah's carrying quads, in the form of two sets of identical twins.

Setting aside what is and isn't possible, the likelihood of Sarah carrying one, two, or more babies is subject to the usual rules of probability. On transfer day, Dr. Kutteh told us that the probabilities broke down by thirds: one-third of women in Sarah's situation would have twins; one third would get a single pregnancy; and one third would get no pregnancy. Two weeks on, we know we're not in the "no pregnancy" group. So there's a ~50% chance that we're in the singleton group, and a ~50% chance we're in the dizygotic twins group.

Beyond that, probabilities get small. Identical twins account for about 3 of every 1000 pregnancies. That's 0.3%. So the probabilities break down like this:

49.85% one baby

49.85% fraternal twins

0.15% identical twins

0.15% triplets, composed of 1 set of identical twins and a fraternal triplet.

The probability of quads of any kind is too small to register at this number of sig figs. And of course the identical twinning numbers here are too big: some identicals form between days 1 and 5, and we know that didn't happen. But this is a good rough guide to the possibility of tour taking home more than two babies this go-round.

The take home message is: because identical twinning is always rare the odds are slim; but because identical twinning does happen and can't be ruled out on the basis of the transfer day, the odds are not zero.

The short answer is: two. The doc transferred two embryos. If they've both survived, then Sarah's carrying twins; if only one has survived, then it's just one baby (for this time).

The longer answer is: well, it depends. There were two blastocysts on Day 5. Most identical twinning is thought to happen at the blastocyst stage between Days 4 and 8. The astute reader will note that 5 is more than 4 but less than 8; this means it is at least possible for a day Day 5 blast to split into monozygotic (identical) twins after the transfer. So it's possible, in the strictest sense of the word, that Sarah's carrying quads, in the form of two sets of identical twins.

Setting aside what is and isn't possible, the likelihood of Sarah carrying one, two, or more babies is subject to the usual rules of probability. On transfer day, Dr. Kutteh told us that the probabilities broke down by thirds: one-third of women in Sarah's situation would have twins; one third would get a single pregnancy; and one third would get no pregnancy. Two weeks on, we know we're not in the "no pregnancy" group. So there's a ~50% chance that we're in the singleton group, and a ~50% chance we're in the dizygotic twins group.

Beyond that, probabilities get small. Identical twins account for about 3 of every 1000 pregnancies. That's 0.3%. So the probabilities break down like this:

49.85% one baby

49.85% fraternal twins

0.15% identical twins

0.15% triplets, composed of 1 set of identical twins and a fraternal triplet.

The probability of quads of any kind is too small to register at this number of sig figs. And of course the identical twinning numbers here are too big: some identicals form between days 1 and 5, and we know that didn't happen. But this is a good rough guide to the possibility of tour taking home more than two babies this go-round.

The take home message is: because identical twinning is always rare the odds are slim; but because identical twinning does happen and can't be ruled out on the basis of the transfer day, the odds are not zero.

Follow-On Test Result

The other day I mentioned that we got a positive pregnancy test. I believe (this technical details are not 100% certain) that the test was a quantitative assay for hCG, and that the numerical result was 120.07 mIU/mL. Following this result we were instructed to come back in for a follow-on test today. The doctors were hoping to see an 80-100% increase in this level in the 48 hours between tests. This near-doubling would nail down the "is she pregnant?" question for sure and certain.

(In addition, this rate of change is commonly used to check for ectopic pregnancy. In our case an ectopic pregnancy is very unlikely; 98% of ectopics occur in the fallopian tubes, which Sarah doesn't have.)

As you might imagine, this post exists to report the result of the follow on test. Drawn this morning, Sarah's blood contains 383.75 mIU/mL hCG. (Again, the unit is somewhat uncertain, but the number is right.) That's well more than a doubling; in fact it's slightly more than a tripling in 48 hours (an increase of 220%, to be precise).

Now, I know your next question, and the answer is: yes, high [hCG] levels and a high rate of increase in [hCG] can indeed suggest the presence of twins. That said, as an indicator this is highly imperfect. The basic problem appears to be that individual variance is very high, so even very wide divergence from the 48hr doubling may simply be individual "noise" rather than a twinning "signal". That said, these test results are definitely adding dramatic tension to the time from now until the ultrasound on the 15th.

(In addition, this rate of change is commonly used to check for ectopic pregnancy. In our case an ectopic pregnancy is very unlikely; 98% of ectopics occur in the fallopian tubes, which Sarah doesn't have.)

As you might imagine, this post exists to report the result of the follow on test. Drawn this morning, Sarah's blood contains 383.75 mIU/mL hCG. (Again, the unit is somewhat uncertain, but the number is right.) That's well more than a doubling; in fact it's slightly more than a tripling in 48 hours (an increase of 220%, to be precise).

Now, I know your next question, and the answer is: yes, high [hCG] levels and a high rate of increase in [hCG] can indeed suggest the presence of twins. That said, as an indicator this is highly imperfect. The basic problem appears to be that individual variance is very high, so even very wide divergence from the 48hr doubling may simply be individual "noise" rather than a twinning "signal". That said, these test results are definitely adding dramatic tension to the time from now until the ultrasound on the 15th.

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

What Now?

Some details: the pregnancy test is quantitative, meaning they measure the concentration of hCG in the blood. For a "positive" test on this day, they're looking for a concentration of 60-70 [somethings --- Sarah doesn't share my affinity for units]. Sarah's result was 120 [somethings]. The nurse describes this as a "good, solid positive."

So what now? Well, drug therapy continues; we'll continue at the 50mg progesterone dose for at least the next two weeks. In addition, Sarah starts some other meds that are also designed to support early pregnancy.

We go back for another test on Friday morning. They're looking for that 120 number to almost double --- to increase by 80% in 48 hours. I'll report back on that result when we have it Friday afternoon.

Meanwhile, we still don't know whether Sarah's carrying one baby or two. We're scheduled to go for an ultrasound and meet with the doctor on the 15th. We should know more about the "one or two" question then.

So what now? Well, drug therapy continues; we'll continue at the 50mg progesterone dose for at least the next two weeks. In addition, Sarah starts some other meds that are also designed to support early pregnancy.

We go back for another test on Friday morning. They're looking for that 120 number to almost double --- to increase by 80% in 48 hours. I'll report back on that result when we have it Friday afternoon.

Meanwhile, we still don't know whether Sarah's carrying one baby or two. We're scheduled to go for an ultrasound and meet with the doctor on the 15th. We should know more about the "one or two" question then.

Positive

We got the call from the nurse about 1:45. The test was positive. It appears we're having at least one baby.

Small Frys

Where were we? It looks like I reported on the embryo transfer, but then never came back and reported on the remaining embryos:

That post is from last Monday, June 21st. We did indeed hear about the disposition of these embryos on Tuesday the 22nd. As it turns out, not only did all five of the lagging-behind embryos make it to the blastocyst stage and go into cryo, but a sixth (and presumed-lost) embryo did as well!

So, as of today we have eight embryos in play: the two that were transferred to Sarah last Monday, and six in FAM's cryo facility.

If you're interested in cost (which I've tried to keep up with through most of these posts), the freezing and first two years of storage cost $785. In purely financial terms, this is a clear winner, because the cost of transferring a couple of frozen embryos is far less than the cost of producing new embryos and transferring those. In subsequent cycles, we'll now be able to skip the entire stimulation/retrieval/fertilization/culture phases and go straight to transfer. There's a huge reduction in cost associated with this change in the procedure: fewer drugs, fewer lab tests, fewer trips to the clinic, fewer needle sticks, etc. If we assume that six frozen embryos are enough to do two future transfers (more on this in a moment), this is a net savings of several thousands of dollars.

Of course the money is a relatively minor concern. (That's not to say trivial; we are talking about a lot of money, from a civil-servant perspective.) The much bigger issue is: these are live humans, and our children to boot. I know, I know: I said there would be no politics. But we see it this way:

1. our actions brought about new, live organisms of H. sapiens;

2. moral humility requires that all live organisms of H. sapiens be treated as persons with an inalienable right to life; so,

3. we have a moral duty to give each of these organisms the best chance at life that we are able to provide.

I know that point 2 is controversial in public discourse, but there's nothing controversial about it in our house. So let's just leave it at that.

In any event, what this adds up to is: all six of the currently-frozen embryos will at some point be transferred to Sarah and get a fair shot at life. So there's the potential that we could have as many as 8 children. This is unlikely, and it's not what we set out to get (we maintain that we'd be happy with one healthy baby) but if that's in the Divine Plan we're happy to work with it.

In addition to these two, five more embryos are still alive and developing. Those five are a little farther behind, and not yet to the blastocyst stage at all. They will either make it to that stage in the next day or they never will. Those that do will go into cryo-preservation (ie, a freezer) for later transfer. We'll hear about how many (if any) go into cryo tomorrow morning.

That post is from last Monday, June 21st. We did indeed hear about the disposition of these embryos on Tuesday the 22nd. As it turns out, not only did all five of the lagging-behind embryos make it to the blastocyst stage and go into cryo, but a sixth (and presumed-lost) embryo did as well!

So, as of today we have eight embryos in play: the two that were transferred to Sarah last Monday, and six in FAM's cryo facility.

If you're interested in cost (which I've tried to keep up with through most of these posts), the freezing and first two years of storage cost $785. In purely financial terms, this is a clear winner, because the cost of transferring a couple of frozen embryos is far less than the cost of producing new embryos and transferring those. In subsequent cycles, we'll now be able to skip the entire stimulation/retrieval/fertilization/culture phases and go straight to transfer. There's a huge reduction in cost associated with this change in the procedure: fewer drugs, fewer lab tests, fewer trips to the clinic, fewer needle sticks, etc. If we assume that six frozen embryos are enough to do two future transfers (more on this in a moment), this is a net savings of several thousands of dollars.

Of course the money is a relatively minor concern. (That's not to say trivial; we are talking about a lot of money, from a civil-servant perspective.) The much bigger issue is: these are live humans, and our children to boot. I know, I know: I said there would be no politics. But we see it this way:

1. our actions brought about new, live organisms of H. sapiens;

2. moral humility requires that all live organisms of H. sapiens be treated as persons with an inalienable right to life; so,

3. we have a moral duty to give each of these organisms the best chance at life that we are able to provide.

I know that point 2 is controversial in public discourse, but there's nothing controversial about it in our house. So let's just leave it at that.

In any event, what this adds up to is: all six of the currently-frozen embryos will at some point be transferred to Sarah and get a fair shot at life. So there's the potential that we could have as many as 8 children. This is unlikely, and it's not what we set out to get (we maintain that we'd be happy with one healthy baby) but if that's in the Divine Plan we're happy to work with it.

Waiting

Sarah had blood drawn for her pregnancy test at 7:45AM this morning. It is now 1:18PM. The last week has been tough, but the last hour has been excruciating. Say what you want about needles and money and car trips and time off work; I think this is the hardest part of the whole process.

Monday, June 21, 2010

When Will We Know?

Next Wednesday, we'll go in at 7:30. Sarah will have blood draw. They'll do a quantitative pregnancy test. That is, they'll measure the concentration of hCG in Sarah's system and determine whether she's pregnant or not. They'll complete the test in the late morning and call us with the result around noon.

Blood Test

Sarah just took a call from the lab; her blood test is finished. Her estrogen and progesterone levels look "beautiful". There are no changes to her medications; we proceed as normal until the pregnancy test next Wednesday.

Probability

We're told the probability of success shakes out in thirds. Given the transfer of two blasts, Sarah's age and health, etc, there's about a 1/3 chance that she'll have twins, about a 1/3 chance that she'll have a single baby, and about a 1/3 chance of going back to the drawing board.

Embryos

So, they transferred these two:

The codes at the bottom [(DBC), (CBC)] are grades. Obviously they're somewhat less-than-stellar. This is because these embryos are a little behind schedule, and just becoming blastocysts. So, the different regions of the blastocyst are still poorly defined and hard to grade. The grades DON'T mean that Sarah is really any less likely to get pregnant. More on that in a moment.

In addition to these two, five more embryos are still alive and developing. Those five are a little farther behind, and not yet to the blastocyst stage at all. They will either make it to that stage in the next day or they never will. Those that do will go into cryo-preservation (ie, a freezer) for later transfer. We'll hear about how many (if any) go into cryo tomorrow morning.

The codes at the bottom [(DBC), (CBC)] are grades. Obviously they're somewhat less-than-stellar. This is because these embryos are a little behind schedule, and just becoming blastocysts. So, the different regions of the blastocyst are still poorly defined and hard to grade. The grades DON'T mean that Sarah is really any less likely to get pregnant. More on that in a moment.

In addition to these two, five more embryos are still alive and developing. Those five are a little farther behind, and not yet to the blastocyst stage at all. They will either make it to that stage in the next day or they never will. Those that do will go into cryo-preservation (ie, a freezer) for later transfer. We'll hear about how many (if any) go into cryo tomorrow morning.

Embryo Transfer

We went in for embryo transfer today. Sarah's routine looked like this:

1. Leave home at 6:20.

2. Arrive at the clinic at 7:50. Have blood drawn for progesterone test.

3. Check in with surgery center at 8:00. Begin drinking water (they need her bladder full for some reason).

4. Move to pre-op room at 8:30, change into surgical gown, socks and hairnet.

5. Meet with doctor at 9:20, get picture of embryos to be transferred.

6. Move to transfer room at 9:35.

7. Transfer. Done by 9:45.

8. Lay in tilted (head-down) operating bed until 10:15.

9. Change and head home. On the road by 10:30.

10. Arrive at home at 12:00. Settle in on couch.

The transfer doesn't take long. They put Sarah on a bed that tilts so her head is down below her hips. Then they pass a catheter through her cervix into her uterus. They use an ultrasound to position the catheter right where they want in the uterus. The embryologist wheels an incubator into the room and loads the embryos into a tub with a growth-medium liquid. Then the doctor flushes the embryos down through the catheter into her uterus. Then they withdraw the catheter, and the embryologist examines it to make sure the embryos aren't still inside it. Then that's it.

1. Leave home at 6:20.

2. Arrive at the clinic at 7:50. Have blood drawn for progesterone test.

3. Check in with surgery center at 8:00. Begin drinking water (they need her bladder full for some reason).

4. Move to pre-op room at 8:30, change into surgical gown, socks and hairnet.

5. Meet with doctor at 9:20, get picture of embryos to be transferred.

6. Move to transfer room at 9:35.

7. Transfer. Done by 9:45.

8. Lay in tilted (head-down) operating bed until 10:15.

9. Change and head home. On the road by 10:30.

10. Arrive at home at 12:00. Settle in on couch.

The transfer doesn't take long. They put Sarah on a bed that tilts so her head is down below her hips. Then they pass a catheter through her cervix into her uterus. They use an ultrasound to position the catheter right where they want in the uterus. The embryologist wheels an incubator into the room and loads the embryos into a tub with a growth-medium liquid. Then the doctor flushes the embryos down through the catheter into her uterus. Then they withdraw the catheter, and the embryologist examines it to make sure the embryos aren't still inside it. Then that's it.

Saturday, June 19, 2010

This Is What You Get For Distrusting Your Husband

I mentioned the other night (Monday) that I gave Sarah an IM shot of hCG. Weirdly, after the shot she decided she was greatly disturbed by the fact that the shot --- wait for it --- didn't hurt enough. No, really; she was three-quarters convinced that the absence of pain from the shot meant I'd done it wrong. She wigged out all night, and didn't relax again until the positive pregnancy test on Tuesday morning.

So I mentioned this to the doctor on Wednesday, and he said "oh, we can fix that." And the fix is this: after the retrieval but before she got dressed, the nurses at the surgery center took a black magic marker and drew targets on Sarah's butt. The "targets" are circles and crosses: the crosses are supposed to roughly mark the track of a major nerve that runs through the area, while the circles are sort of drop-zones for the shots.

So I mentioned this to the doctor on Wednesday, and he said "oh, we can fix that." And the fix is this: after the retrieval but before she got dressed, the nurses at the surgery center took a black magic marker and drew targets on Sarah's butt. The "targets" are circles and crosses: the crosses are supposed to roughly mark the track of a major nerve that runs through the area, while the circles are sort of drop-zones for the shots.

Progesterone

Meanwhile, as of Thursday we started a new series of shots. This is progesterone, which you can think of as "pregnancy hormone"; it's primary role is to initiate all of the changes that a woman's body goes through during pregnancy. Now, a couple of things about that:

1. You should remember that in the normal course of business, Sarah would be pregnant right now; the 8-cell embryo would be somewhere in her fallopian tube or uterus, and her body would be beginning to respond to this reality. Because our 8-cell emrbyo(s) happens to be in a neighboring state, we have to make some of these changes to Sarah's body by hand. Hence, the injections of progesterone.

2. Because of the special circumstances of conception, it's imperative that we maximize the chance of successful implantation and pregnancy. This means, among other things, that we want "overkill" on a number of pro-pregnancy measures. Again, this is a case for injecting larger-than-strictly-natural doses of progesterone into Sarah.

The shot is IM. It goes in the hip, just like the hCG shot. It uses the same 25G 1.5in needle I used for hCG. The bad news is, the hormone comes dissolved in some kind of oil. Have you ever had a nice, viscous IM tetanus shot? No fun, right? Now imagine getting one very night for a few weeks. Suck. But it's got to be done.

1. You should remember that in the normal course of business, Sarah would be pregnant right now; the 8-cell embryo would be somewhere in her fallopian tube or uterus, and her body would be beginning to respond to this reality. Because our 8-cell emrbyo(s) happens to be in a neighboring state, we have to make some of these changes to Sarah's body by hand. Hence, the injections of progesterone.

2. Because of the special circumstances of conception, it's imperative that we maximize the chance of successful implantation and pregnancy. This means, among other things, that we want "overkill" on a number of pro-pregnancy measures. Again, this is a case for injecting larger-than-strictly-natural doses of progesterone into Sarah.

The shot is IM. It goes in the hip, just like the hCG shot. It uses the same 25G 1.5in needle I used for hCG. The bad news is, the hormone comes dissolved in some kind of oil. Have you ever had a nice, viscous IM tetanus shot? No fun, right? Now imagine getting one very night for a few weeks. Suck. But it's got to be done.

Day 4

Tomorrow will be Day 4. A lot will happen in the Petri dish, but nothing will happen in the Hopkins House. That is, we will not get a call from the embryologist, and will not learn anything new about the status of the embryos. In fact, as I understand it she won't even take the embryos out of their incubator.

Now, I know what you're thinking, but this has nothing to do with the fact that tomorrow's Sunday. Apparently cell division accelerates rapidly from here on out; where as we were seeing 1 to 2 division per day, the cells will undergo a number of cell divisions on Day 4 as they transition from an undifferentiated blob of 8 cells on Day 3 to a structured, 250+ cell blastocyst on Day 5. All this rapid change makes it difficult to make any assessments of their quality on Day 4.

On Monday, our transfer is scheduled for 9:15. We're supposed to be there at the clinic at 7:50, so that they can draw blood and do other prep in advance of the transfer. The transfer itself only lasts a few moments, so if everything goes off as scheduled we should be on the road home by 10. More on this as it happens.

Now, I know what you're thinking, but this has nothing to do with the fact that tomorrow's Sunday. Apparently cell division accelerates rapidly from here on out; where as we were seeing 1 to 2 division per day, the cells will undergo a number of cell divisions on Day 4 as they transition from an undifferentiated blob of 8 cells on Day 3 to a structured, 250+ cell blastocyst on Day 5. All this rapid change makes it difficult to make any assessments of their quality on Day 4.

On Monday, our transfer is scheduled for 9:15. We're supposed to be there at the clinic at 7:50, so that they can draw blood and do other prep in advance of the transfer. The transfer itself only lasts a few moments, so if everything goes off as scheduled we should be on the road home by 10. More on this as it happens.

Day 3

Today is Day 3. That means today was a possible transfer day, but it turns out that we're waiting for Day 5 to do the transfer. So, in the meantime we got a call with a status update on the embryos. Today it looks even better than yesterday:

6 embryos at Grade 1

7 embryos at Grade 2

1 embryo at Grade 3.

Note that this is an improvement from Friday, when only three of the embryos merited a 1. What's more, we're told that the Grade 3 has gotten this grade because it's straggling in term of number of cells --- they're now expected to be 8 cells --- but that some of the cells are multi-nucleated, which means they may be about to divide again. Apparently some embryos of this type will indeed make it through the next few days and become "transferrable" on Day 5.

6 embryos at Grade 1

7 embryos at Grade 2

1 embryo at Grade 3.

Note that this is an improvement from Friday, when only three of the embryos merited a 1. What's more, we're told that the Grade 3 has gotten this grade because it's straggling in term of number of cells --- they're now expected to be 8 cells --- but that some of the cells are multi-nucleated, which means they may be about to divide again. Apparently some embryos of this type will indeed make it through the next few days and become "transferrable" on Day 5.

Day 2

On Day 1 (Thursday) all we learn is the number of eggs that fertilized successfully. That number turned out to be big: 14. On Day 2 (Friday) we get more information: by then, the embryos have developed enough that they start to diverge in quality. So when the embryologist calls on Day 2, she reports not only how many embryos continue to develop, but a grade for each one.

For Days 2 and 3, the grading scale is a simple 1-5 overall grade where 1 is outstanding, 3 is average, and 5 is not likely to survive. On Day 2, they're looking for embryos to be 4 cells. The grade is based in part on whether there has been adequate division (ie, whether there are in fact 4 cells) and then in part on the subjective quality of the cells. The principle "quality" concern is with fragmentation: each time a cell divides, little pieces of cell break off and get loose. The less of this fragmentation you see in an embryo, the better it is. So each day the embryologist gets the embryos out of the incubator and puts them literally under a microscope, which she uses to give them a good once-over and assign each one a grade.

So, this is the way we graded out on Friday:

3 4-cell embryos at Grade 1

4 4-cell embryos at Grade 2

1 3-cell embryo at Grade 2

5 2-cell embryos at Grade 2

1 2-cell embryo at Grade 3

Recall that Grade 1 is Outstanding quality, Grade 2 is Good, and Grade 3 is Average. So as of Friday, we had 13 embryos of good-to-outstanding quality and 1 of average quality.

As a result, it was decided yesterday that we'll wait for a Day 5 transfer. This will allow the embryos time to differentiate themselves; that is, there will be more time for the differences between the best of them to become noticeable. As we understand it, this means each individual embryo transferred will have a better chance of implanting and growing into a baby.

For Days 2 and 3, the grading scale is a simple 1-5 overall grade where 1 is outstanding, 3 is average, and 5 is not likely to survive. On Day 2, they're looking for embryos to be 4 cells. The grade is based in part on whether there has been adequate division (ie, whether there are in fact 4 cells) and then in part on the subjective quality of the cells. The principle "quality" concern is with fragmentation: each time a cell divides, little pieces of cell break off and get loose. The less of this fragmentation you see in an embryo, the better it is. So each day the embryologist gets the embryos out of the incubator and puts them literally under a microscope, which she uses to give them a good once-over and assign each one a grade.

So, this is the way we graded out on Friday:

3 4-cell embryos at Grade 1

4 4-cell embryos at Grade 2

1 3-cell embryo at Grade 2

5 2-cell embryos at Grade 2

1 2-cell embryo at Grade 3

Recall that Grade 1 is Outstanding quality, Grade 2 is Good, and Grade 3 is Average. So as of Friday, we had 13 embryos of good-to-outstanding quality and 1 of average quality.

As a result, it was decided yesterday that we'll wait for a Day 5 transfer. This will allow the embryos time to differentiate themselves; that is, there will be more time for the differences between the best of them to become noticeable. As we understand it, this means each individual embryo transferred will have a better chance of implanting and growing into a baby.

Fertilization

Well, what we were told on Wednesday:

turned out to be spot on. Of the 21 total eggs retrieved, 14 fertilized successfully. As of Thursday afternoon, we had 14 one-cell embryos (ie, zygotes).

I'm told the doctor recovered 21 eggs, and that "at least 2/3 of them" look really good.

turned out to be spot on. Of the 21 total eggs retrieved, 14 fertilized successfully. As of Thursday afternoon, we had 14 one-cell embryos (ie, zygotes).

Wednesday, June 16, 2010

Retrieval

Retrieval went well today. We left home at 5:30, arrived at the clinic a little before 7:00, and were en route home by 11:00. I'm told the doctor recovered 21 eggs, and that "at least 2/3 of them" look really good.

The eggs were combined with sperm this afternoon, and will fertilize overnight. (Not all of them are likely to fertilize.) We'll get a call from the embryologist tomorrow afternoon, at which time we'll hear how many embryos we've got.

Transfer is either Day 3 or Day 5. Tomorrow is Day 1; that means transfer will be either Saturday or Monday.

The eggs were combined with sperm this afternoon, and will fertilize overnight. (Not all of them are likely to fertilize.) We'll get a call from the embryologist tomorrow afternoon, at which time we'll hear how many embryos we've got.

Transfer is either Day 3 or Day 5. Tomorrow is Day 1; that means transfer will be either Saturday or Monday.

Tuesday, June 15, 2010

Egg Retrieval and Conception

As described below, the stimulation phase of our IVF cycle came to an end on Monday night, when Sarah got a nice big shot of hCG. Now, the next step is to get the mature eggs out of her ovaries into the Petri dishes where they will be fertilized. The process of getting the eggs is called "egg retrieval" and it happens bright and early tomorrow morning.

The procedure is relatively simple; the doctor uses an ultrasound machine to guide a long needle to Sarah's ovaries, then punches it into each ovarian follicle. Once he's "stuck" a follicle, he sucks out the entire contents of the follicle, which should include a mature secondary oocyte (egg). Hopefully, due to the stimulation process, there will be a large number of these mature eggs: say, a dozen or more. (In 2006 they recovered 14 eggs.)

Sarah is under general anesthesia for the whole process, which is conducted in an outpatient surgery center and takes less than an hour. We'll leave home at 5:30; I expect we'll be back around lunch. There is no recovery to speak of, though it does take a while to fully shake off the effects of the anesthesia; I expect her to be sleepy all day Wednesday but fully back to normal on Thursday.

Meanwhile, tomorrow is also the day I make my genetic contribution. I do this while Sarah's in recovery. Once they have my fluid, it works like this: an embryologist put a drop of it in a Petri dish filled with a nutrient-rich growth medium. Then an egg is added to the drop, and the dish is covered and put in an incubator.

24 hours later, the embryologist check in and sees how many of the eggs successfully fertilized. As a rule, it will not be all of them; in 2006 11 of the 14 recovered eggs were fertilized. We'll get a phone call from the embryologist Thursday afternoon; at that time she'll tell us how many zygotes we've conceived.

The procedure is relatively simple; the doctor uses an ultrasound machine to guide a long needle to Sarah's ovaries, then punches it into each ovarian follicle. Once he's "stuck" a follicle, he sucks out the entire contents of the follicle, which should include a mature secondary oocyte (egg). Hopefully, due to the stimulation process, there will be a large number of these mature eggs: say, a dozen or more. (In 2006 they recovered 14 eggs.)

Sarah is under general anesthesia for the whole process, which is conducted in an outpatient surgery center and takes less than an hour. We'll leave home at 5:30; I expect we'll be back around lunch. There is no recovery to speak of, though it does take a while to fully shake off the effects of the anesthesia; I expect her to be sleepy all day Wednesday but fully back to normal on Thursday.

Meanwhile, tomorrow is also the day I make my genetic contribution. I do this while Sarah's in recovery. Once they have my fluid, it works like this: an embryologist put a drop of it in a Petri dish filled with a nutrient-rich growth medium. Then an egg is added to the drop, and the dish is covered and put in an incubator.

24 hours later, the embryologist check in and sees how many of the eggs successfully fertilized. As a rule, it will not be all of them; in 2006 11 of the 14 recovered eggs were fertilized. We'll get a phone call from the embryologist Thursday afternoon; at that time she'll tell us how many zygotes we've conceived.

Relax; This Is Not What It Appears To Be

Well, it sort of is. It appears to be a positive pregnancy test. And it is. But it doesn't mean Sarah is pregnant. Allow me to explain.

The predictions made on Sunday held up. On Monday we went in for a blood draw (no ultrasound). The results of this E2 test told our doc that Sarah's eggs were mature and ready to harvest. So, yesterday afternoon they called and scheduled retrieval.

Put in the broadest terms, woman's cycle looks like this:

1. End menstruation.

2. Begin building up a new uterine lining while egg matures.

3. Ovulate.

4. Wait to see if egg is fertilized.

6. Begin menstruation.

Now, imagine that during step 4, the egg is in fact fertilized and embeds in the uterine lining. The last thing you want is for the uterine lining to be shed; it would take the developing embryo with it. So you need some signal from the developing embryo to the rest of the body --- something that says:

HOLD EVERYTHING, I AM HERE!

That signal comes in the form of human chorionic gonadotropin, or hCG. This is a hormone that is only produced in the event of pregnancy, and when present it brings the woman's menstrual cycle to a screeching halt. In other words, hCG is a kind of switch that works to shift a woman's hormonal system from "normal" to "pregnant".

(It's also been in the news lately, as the compound that got linebacker Brian Cushing suspended from the Texans and nearly cost him his Defensive Rookie of the Year award. Its presence in a man indicates one of two things: he either has testicular cancer, or has injected the hormone as part of a program of steroid use. Cushing maintains that he is a medical marvel whose body must somehow be producing hCG in the absence of any cancer. He is lying.)

Produced in a laboratory and packed into a kit, it looks like this:

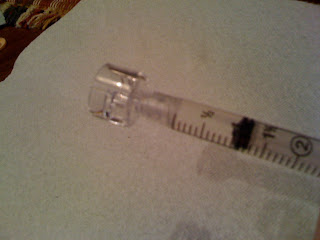

It's one of those binary jobs like the Menopur: the big vial on the left is sterile water; the smaller vial on the right contains crystalline hCG. To prepare the injection, you take the syringe, stick it in the vial of water, and draw 1mL. Then you pull the syringe out of the water vial, stick it in the vial of powdered hCG, and inject the water into the medicine. In this case, the amount of medicine to be dissolved (look closely: it's 10,000 units) is large enough that dissolution is slower and takes a little more agitation. Once dissolved, the solution is drawn back up into the syringe, and the broad needle swapped out for a 27 guage, 1.5in needle. The prepared shot looks like this:

So this looks a lot like the prepared Menopur shot --- except that in this case, that long needle is going to go all the way in. The shot is meant for intra-muscular (IM) delivery, meaning the needle goes all the way through the skin and underlying fat and into the muscle. We do this in Sarah's upper hip, where the muscle is big and thick.

The technique is simple: wipe the injection site with a sterile alcohol pad, press it flat, stick the needle all the way in, pull back slightly (to check for blood, and thereby ensure you haven't inadvertently stuck the needle into a vein; you don't want to accidentally deliver the shot intravenously), and then press the plunger and deliver the med. It's over lickety-split.

The pregnancy test is a check to make sure the injection worked. Over-the-counter pregnancy tests are yes-or-no checks for the presence of hCG; the positive test indicates that she's got a good dose of hCG in her blood. In other words, that means I correctly administered the shot and her cycle is safely halted for egg retrieval, embryo transfer and early pregnancy.

Sunday, June 13, 2010

Sunday SITREP

We went in for blood test & ultrasound this morning (yes, on Sunday). The follicles on the left and right ovaries have diverged somewhat: those on the right now range from 17-20mm in size; those on the left range from 14-17mm. The doctor looked at this and today's E2 level and decided to let stimulation go on one more day. So we have Follistim and Lupron tonight, and Menopur in the morning. As I understand it, the expectation (subject to change after the blood test tomorrow morning) is that we'll then do the hCG injection tomorrow evening and have retrieval on Wednesday.

Friday, June 11, 2010

Progress Report

As I mentioned below, we've had a number of blood tests and ultrasounds this week. The way this works is, we arrive at the clinic at 7:30 AM. (This, incidentally, means we leave home at 6:00AM; again, the clinic is in Memphis.) Sarah has blood drawn and (since Wednesday) an ultrasound; we're on the road home by 8:00. We typically get back to town by 9:15 or so (traffic differences), and go straight to work.

Meanwhile, the lab is doing an E2 test and the ultrasound tech is preparing a report for Dr. Ke. Sometime around midday, the doctor and nurse meet and discuss our progress, and make two decisions: what (if any) changes to make in the injection regimen; and when we need to come back in.

Friday night we started stimulation. The original injection regimen was: 75 units (ie, 1 vial) of Menopur in the morning, plus 0.05 mL of Lupron and 125 units of Follistim in the evening. The precise timings were up to us, but the morning and evening injections need to be 12 hours apart. We chose 7:30, AM and PM. Every twelve hours at 7:25, Sarah's phone starts playing the ABBA song "Honey Honey" (I think the version sung by whats-her-name in the Mama Mia movie, technically speaking). When that happens we stop everything we're doing and prep the relevant shots, then give them right at 7:30. We do this religiously, and very rarely miss an injection time by more than about 30 seconds.

At this point the astute reader will have noted a conflict: we're giving injections at 7:30AM, but we're also arriving at the clinic for tests at 7:30 AM. The resolution is simple: on test days, we mix and inject the Menopur in the car right before we walk in the doctor's office. Yes, this means I shoot Sarah up right there in the parking lot. It's class all over, I tell you.

Anyway, Monday morning Sarah had blood drawn. Her E2 must have looked a shade low, because the nurse called on Monday afternoon and told us to up the Follistim dosage sightly, from 125 units to 150 units.

Wednesday we went in for both E2 and ultrasound. In the ultrasound, things looked good: all of Sarah's follicles were between 9 and 12 mm in diameter. And the E2 must have been good too, because the drug doses were unchanged. We were told to come in on Friday morning, as expected.

Friday (ie, today) was another E2 and ultrasound day. Interestingly, I think we got the broke-ass ultrasound machine today, because it was hard to see anything. (Sarah's right ovary, which is usually crisply defined and easy to see, was hard to make out; her left, which is hazy under the best of circumstances, was nearly invisible.) What the tech could see was good news; Sarah's follicles had grown, from the previous 9-12mm bracket to 12-15mm.

That said, when we left Sarah was feeling discouraged, about two things: first, that the tech couldn't see nearly as many follicles as the other tech did with the other machine on Wednesday; and second, that we were told that her follicles are growing more slowly in this cycle than they did during the 06 cycle. Interestingly, what I heard the tech say was "you're progressing a little slower, and that is perfectly OK", while Sarah apparently heard something like "you're progressing a little slower, and that is THE END OF THE WORLD." Later, in the car, I would insist that what I heard was much closer to reality, but she would have none of it. The ride home was very quiet.

Well, guess who was right. Much as I hate to admit it, the party closer to reality was .... well, actually, it was me, and I don't "hate to admit it" at all. The nurse called about 3, and it turns out that we're in perfectly good shape. There are no changes in the medications, and we go back in on Sunday --- at the practically civilized time of 8:00AM.

So that's where we're at: the follicles are 12-15mm. They grew 3mm in two days (from 9-12 on Wed to 12-15 today), and we're looking for them to be 18-20 mm for retrieval. Assuming linear growth (an assumption that I base on absolutely nothing --- just so's you know), we'd be talking about retrieval on Tuesday or so. Backing up this theory, we ran low on Menopur late this weekend were told by the nurse to order more -- but only enough to take us through Monday. So it looks like we're at least tentatively planning on wrapping up stimulation Monday or Tuesday, and doing retrieval Tuesday or Wdensday of next week.

Hopefully we'll know more concretely on Sunday.

Meanwhile, the lab is doing an E2 test and the ultrasound tech is preparing a report for Dr. Ke. Sometime around midday, the doctor and nurse meet and discuss our progress, and make two decisions: what (if any) changes to make in the injection regimen; and when we need to come back in.

Friday night we started stimulation. The original injection regimen was: 75 units (ie, 1 vial) of Menopur in the morning, plus 0.05 mL of Lupron and 125 units of Follistim in the evening. The precise timings were up to us, but the morning and evening injections need to be 12 hours apart. We chose 7:30, AM and PM. Every twelve hours at 7:25, Sarah's phone starts playing the ABBA song "Honey Honey" (I think the version sung by whats-her-name in the Mama Mia movie, technically speaking). When that happens we stop everything we're doing and prep the relevant shots, then give them right at 7:30. We do this religiously, and very rarely miss an injection time by more than about 30 seconds.

At this point the astute reader will have noted a conflict: we're giving injections at 7:30AM, but we're also arriving at the clinic for tests at 7:30 AM. The resolution is simple: on test days, we mix and inject the Menopur in the car right before we walk in the doctor's office. Yes, this means I shoot Sarah up right there in the parking lot. It's class all over, I tell you.

Anyway, Monday morning Sarah had blood drawn. Her E2 must have looked a shade low, because the nurse called on Monday afternoon and told us to up the Follistim dosage sightly, from 125 units to 150 units.

Wednesday we went in for both E2 and ultrasound. In the ultrasound, things looked good: all of Sarah's follicles were between 9 and 12 mm in diameter. And the E2 must have been good too, because the drug doses were unchanged. We were told to come in on Friday morning, as expected.

Friday (ie, today) was another E2 and ultrasound day. Interestingly, I think we got the broke-ass ultrasound machine today, because it was hard to see anything. (Sarah's right ovary, which is usually crisply defined and easy to see, was hard to make out; her left, which is hazy under the best of circumstances, was nearly invisible.) What the tech could see was good news; Sarah's follicles had grown, from the previous 9-12mm bracket to 12-15mm.

That said, when we left Sarah was feeling discouraged, about two things: first, that the tech couldn't see nearly as many follicles as the other tech did with the other machine on Wednesday; and second, that we were told that her follicles are growing more slowly in this cycle than they did during the 06 cycle. Interestingly, what I heard the tech say was "you're progressing a little slower, and that is perfectly OK", while Sarah apparently heard something like "you're progressing a little slower, and that is THE END OF THE WORLD." Later, in the car, I would insist that what I heard was much closer to reality, but she would have none of it. The ride home was very quiet.

Well, guess who was right. Much as I hate to admit it, the party closer to reality was .... well, actually, it was me, and I don't "hate to admit it" at all. The nurse called about 3, and it turns out that we're in perfectly good shape. There are no changes in the medications, and we go back in on Sunday --- at the practically civilized time of 8:00AM.

So that's where we're at: the follicles are 12-15mm. They grew 3mm in two days (from 9-12 on Wed to 12-15 today), and we're looking for them to be 18-20 mm for retrieval. Assuming linear growth (an assumption that I base on absolutely nothing --- just so's you know), we'd be talking about retrieval on Tuesday or so. Backing up this theory, we ran low on Menopur late this weekend were told by the nurse to order more -- but only enough to take us through Monday. So it looks like we're at least tentatively planning on wrapping up stimulation Monday or Tuesday, and doing retrieval Tuesday or Wdensday of next week.

Hopefully we'll know more concretely on Sunday.

Follistim: A Photo Essay

In the evenings we do Lupron, which we already covered, and Follistim. Follistim comes in a handy-dandy pen gizmo and is way more convenient than any of the other drugs. It's also wildly expensive. Here's the kit:

The blue case holds the injection pen; the cardboard box holds a cartridge of drug and some disposable needles for the pen. When we open the case, the pen kit looks like this:

So you've got the pen, you've got some needles (in the little pink things), you've got a place to carry some sterile wipes --- all in a nice zip-up case. How convenient! Er, except that once the pen is loaded with drug, the whole shooting match has to be stored in a refrigerator. Which makes it significantly less convenient, and sort of defies the whole point of the snazzy carrying-case. Well, whatever.

The pen itself is a lot like an ink pen with a reloadable cartridge:

So the piece at left is just a cap, liek the cap on any pen. At top is the bottom of the pen; you stick the catridge in from right to left, then screw on the bit with the plunger. The cartridge itself is the glass thing at bottom. Close-up, it looks like this:

It's small. Here it is loaded in the pen and held in my hand. The cartridge is about the length of the last two digits of my pinky finger, and much, much narrower; it's maybe 5mm in diameter. The list price for this 600 unit cartridge is more than $500. The good news is, they do usually have some extra medicine in them; we got >700 units out of the first "600 unit" cartridge.

Once the cartridge is loaded in the pen, you need to put a needle on it. The needles come in these little containers that look like miniature versions of the creamer containers at Denny's:

You take the paper top off (again, it's like a creamer container) and just screw the whole thing on the end of the pen:

Then pull off the creamer-container and an internal needle cover to expose the needle. It's very small; this is not only a sub-q shot, it's one I haven't kludged together from old IM needles.

With the needle on, it's dial-a-dose: you turn the know on the end of the pen until the desired dose appears in the window. We started out with a 125 unit dose; now we're up to 150.

Ready to go, the pen looks like this:

To use it, I stick it in Sarah's belly and push the plunger down with my thumb. The dose injected is determined in advance by the dial-a-dose thingy, so it's stress-free (for me). In the event that the cartridge runs out in the middle of an injection, it's no big deal; you just note on the dial how much drug was left to be injected, reload a new cartridge and needle, and finish the injection. Of course, this means another stick, which Sarah doesn't care for. But them's the breaks; given the expense of this stuff, you really really want to use every bit of it.

The blue case holds the injection pen; the cardboard box holds a cartridge of drug and some disposable needles for the pen. When we open the case, the pen kit looks like this:

So you've got the pen, you've got some needles (in the little pink things), you've got a place to carry some sterile wipes --- all in a nice zip-up case. How convenient! Er, except that once the pen is loaded with drug, the whole shooting match has to be stored in a refrigerator. Which makes it significantly less convenient, and sort of defies the whole point of the snazzy carrying-case. Well, whatever.

The pen itself is a lot like an ink pen with a reloadable cartridge:

So the piece at left is just a cap, liek the cap on any pen. At top is the bottom of the pen; you stick the catridge in from right to left, then screw on the bit with the plunger. The cartridge itself is the glass thing at bottom. Close-up, it looks like this:

It's small. Here it is loaded in the pen and held in my hand. The cartridge is about the length of the last two digits of my pinky finger, and much, much narrower; it's maybe 5mm in diameter. The list price for this 600 unit cartridge is more than $500. The good news is, they do usually have some extra medicine in them; we got >700 units out of the first "600 unit" cartridge.

Once the cartridge is loaded in the pen, you need to put a needle on it. The needles come in these little containers that look like miniature versions of the creamer containers at Denny's:

You take the paper top off (again, it's like a creamer container) and just screw the whole thing on the end of the pen:

Then pull off the creamer-container and an internal needle cover to expose the needle. It's very small; this is not only a sub-q shot, it's one I haven't kludged together from old IM needles.

With the needle on, it's dial-a-dose: you turn the know on the end of the pen until the desired dose appears in the window. We started out with a 125 unit dose; now we're up to 150.

Ready to go, the pen looks like this:

To use it, I stick it in Sarah's belly and push the plunger down with my thumb. The dose injected is determined in advance by the dial-a-dose thingy, so it's stress-free (for me). In the event that the cartridge runs out in the middle of an injection, it's no big deal; you just note on the dial how much drug was left to be injected, reload a new cartridge and needle, and finish the injection. Of course, this means another stick, which Sarah doesn't care for. But them's the breaks; given the expense of this stuff, you really really want to use every bit of it.

Menopur: A Photo Essay

So this is the "kit" for our morning Menopur injection:

It's actually very ad hoc, being an amalgam of new drugs and old (from the Ainsleigh cycle) paraphernalia. Clockwise from top left, we have: sterile alcohol pads to clean the vials and injection sites; the syringe, prepackages with a needle that's much too big and so never used; a Q-Cap (see below); the vials of medicine and diluant (ditto); and the actual needle we'll use (in the center).

This particular medicine comes as a powder. I'm not totally sure why. It seems likely that the drug is not stable in solution; both the Follistim and Lupron have to be refrigerated to keep from decaying, so perhaps the crystalline form can be stored longer and cheaper, saving the manufacturer and distributors money. Also, this packaging makes the concentration of the injected solution adjustable. When you buy solutions like Follistim, the only way to get a bigger dose of the drug is to inject a larger volume of the solution. With the Menopur, you can get a larger dose by dissolving multiple vials of crystalling drug in a single dose of the saline diluant. Of course, the flip side is that the volumes we're dealing with here are much greater; 1 mL of Menopur solution vs. 0.05mL of Lupron or some similarly small volume of Follistim. So it seems like the stability thing is the most likely explanation.

In any case, the technique here is to use this little doodad called a Q-Cap to mix the saline solution (brown label) with the powdered drug (white label). First, the needle that came with the syringe is removed and the Q-Cap screwed on in its place:

It's hard to see, but the Q-Cap has an outer shell that clips over the lip of the drug/diluant vial, and an inner spike that punches through the rubber top of the sterile vial. So, the syringe clips over the vial like so:

One draws 1mL or so of the saline back into the syringe, then unclips the Q-Cap from the diluant vial:

and clips it to the drug vial:

Even the tiniest amount of diluant dissolves the drug powder completely:

the resulting mixture is then drawn back up into the syringe, and the Q-Cap unscrewed and discarded:

The injection needle is attached, and we're ready to go.

For scale, here's what the shot looks like in my hand:

Note that this needle is actally much too big. The shot is subcutaneous, which is a fancy way to say it goes into the fat just under your skin. For this the needle really only neds to be a half inch long. However, we had these 1.5 inch needles laying around, and we're trying to cut costs wherever we can. So we decided to just go with it. My brilliant plan? Only stick the 1.5in needle a third of the way in. Presto, a half-inch needle. How do you like them apples.

Anyway the shot goes lickety-split, but because of the volume it hurts Sarah more and causes more bruising. The poor girl has quite the pattern of bruises across her belly, but she's hanging in there.

It's actually very ad hoc, being an amalgam of new drugs and old (from the Ainsleigh cycle) paraphernalia. Clockwise from top left, we have: sterile alcohol pads to clean the vials and injection sites; the syringe, prepackages with a needle that's much too big and so never used; a Q-Cap (see below); the vials of medicine and diluant (ditto); and the actual needle we'll use (in the center).

This particular medicine comes as a powder. I'm not totally sure why. It seems likely that the drug is not stable in solution; both the Follistim and Lupron have to be refrigerated to keep from decaying, so perhaps the crystalline form can be stored longer and cheaper, saving the manufacturer and distributors money. Also, this packaging makes the concentration of the injected solution adjustable. When you buy solutions like Follistim, the only way to get a bigger dose of the drug is to inject a larger volume of the solution. With the Menopur, you can get a larger dose by dissolving multiple vials of crystalling drug in a single dose of the saline diluant. Of course, the flip side is that the volumes we're dealing with here are much greater; 1 mL of Menopur solution vs. 0.05mL of Lupron or some similarly small volume of Follistim. So it seems like the stability thing is the most likely explanation.

In any case, the technique here is to use this little doodad called a Q-Cap to mix the saline solution (brown label) with the powdered drug (white label). First, the needle that came with the syringe is removed and the Q-Cap screwed on in its place:

It's hard to see, but the Q-Cap has an outer shell that clips over the lip of the drug/diluant vial, and an inner spike that punches through the rubber top of the sterile vial. So, the syringe clips over the vial like so:

One draws 1mL or so of the saline back into the syringe, then unclips the Q-Cap from the diluant vial:

and clips it to the drug vial:

Even the tiniest amount of diluant dissolves the drug powder completely:

the resulting mixture is then drawn back up into the syringe, and the Q-Cap unscrewed and discarded:

The injection needle is attached, and we're ready to go.

For scale, here's what the shot looks like in my hand:

Note that this needle is actally much too big. The shot is subcutaneous, which is a fancy way to say it goes into the fat just under your skin. For this the needle really only neds to be a half inch long. However, we had these 1.5 inch needles laying around, and we're trying to cut costs wherever we can. So we decided to just go with it. My brilliant plan? Only stick the 1.5in needle a third of the way in. Presto, a half-inch needle. How do you like them apples.

Anyway the shot goes lickety-split, but because of the volume it hurts Sarah more and causes more bruising. The poor girl has quite the pattern of bruises across her belly, but she's hanging in there.

Stimulus

So, as of last Friday (June 11th) we've entered the stimulation phase of the IVF process. The basic idea is: hyper-stimulate Sarah's ovaries so that a large number of eggs begin maturing. Over a span of 10 days or so, the eggs develop rapidly; then, when they're just about to be released, the doc goes in and "retrieves" them for fertilization in the Petri dish. More on that later.

During the stimulation phase, Sarah takes a combination of hormone injections. In the morning, she takes Menopur, a so-called "menotropin", meaning a mixture of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). Together, these hormones stimulate the development of follicles, the structures that house eggs as they develop and prepare for fertilization. In the evening she takes a larger dose of FSH in the form of Follistim, and a smaller dose of Lupron, which as we discussed before is an LH agonist.

The process is monitored in two ways. The first is easy to understand: Sarah has ultrasounds exams, in which a technician uses the ultrasound machine to look at her ovaries and count the number of follicles. As the follicles get larger, the tech will not only count them but measure their size. The ideal result from one of these exams is a finding that:

1. there are lots of follicles;

2. they're bigger than they were in the previous exam; and

3. they're all about the same size.

This is all very intuitive, right? You want lots of eggs to fertilize; you want them to be growing and maturing; you want them all to be ready at the same time. So, what's ready? Well, we're looking for the follicles to grow to somewhere right around 2.0cm in diameter. If you're big like me, that's about the size of your thumbnail. If you're small like Sarah, it's more like the size of you big toenail.

In addition to the ultrasounds, Sarah has blood drawn regularly. The draw is for an estradiol (E2) assay. The idea is, we want to see E2 levels going up and up and up. The slope of this curve tells the medical team that the eggs are developing on schedule.

So what do the words "frequent" and "regular" mean in this context? Well, we went for a "baseline" ultrasound and E2 test on June 1st. This was the low point in Sarah's cycle; it tells the docs what her ovaries and hormone levels look like sans stimulation. On Friday the 4th, we started the stimulation phase: Menopur in the morning, Lupron and Follistim in the evening. We went for the first blood draw on Monday the 7th. Then we went for blood tests on Wednesday and Friday, and we go again on Sunday. The first ultrasound was on Wednesday the 9th; we had another Friday and will have a third on Sunday. All told, then, "frequent" means: at least every other day. As retrieval gets closer, it may become every day; it won't surprise me if after Sundays tests we're scheduled to go for more tests on Monday.

More on the results of these tests momentarily.

During the stimulation phase, Sarah takes a combination of hormone injections. In the morning, she takes Menopur, a so-called "menotropin", meaning a mixture of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). Together, these hormones stimulate the development of follicles, the structures that house eggs as they develop and prepare for fertilization. In the evening she takes a larger dose of FSH in the form of Follistim, and a smaller dose of Lupron, which as we discussed before is an LH agonist.

The process is monitored in two ways. The first is easy to understand: Sarah has ultrasounds exams, in which a technician uses the ultrasound machine to look at her ovaries and count the number of follicles. As the follicles get larger, the tech will not only count them but measure their size. The ideal result from one of these exams is a finding that:

1. there are lots of follicles;

2. they're bigger than they were in the previous exam; and

3. they're all about the same size.